M. Kat Anderson’s Tending the Wild has completely revolutionized my understanding of pre-Columbian indigenous land management. Turns out that much of the U.S. was actively managed as a food producing ecosystem! I’ve been researching the topic quite a bit lately and have done some research for the Woodbine Ecology Center about Colorado history (see article below).

Here’s a video on indigenous management that I prepared based on my work for Woodbine.

Some Ecological Aspects of Northeast American Indian Agroforestry Practices

Indigenous Uses and Management of Oaks of the Farm Western United States

Here’s a video on our experience growing out ancient eastern North American crops in our garden in 2011.

Here’s an excerpt from a publication I’m preparing for for the Woodbine Ecology Center:

Native American Management

and

Eco-Cultural Restoration in Colorado

by Eric Toensmeier

This is an excerpt from a publication under development by the Woodbine Ecology Center. Woodbine’s goal is eco-cultural restoration, bringing back the traditions of indigenous management that shaped the landscape for thousands of years. Their goal is to use these traditional species and ecosystem management practices to contribute to indigenous self-determination, decolonizing the diet, and ecological restoration that embraces traditional indigenous management practices. Being located at the edge between the Rocky Mountains and the prairies, Woodbine has many species to draw on as well as a fascinating history to reconstruct.

The first phase is to draw on books like Daniel Moerman’s Native American Ethnobotany and other resources to gather additional information about useful species of the region and what is known of their traditional management. Plans for later phases include interviews with indigenous people who actively manage or historically managed these species and landscapes, establishment of more species and practices at Woodbine, and development of regenerative enterprises for economic development.

Forms of Indigenous Management

In recent decades there has been an increasing acknowledgement of indigenous management of native plants and ecosystems in academic, land management, and ecological restoration circles. An important voice in this movement has been M. Kat Anderson, whose Tending the Wild: Native American Knowledge and the Management of California’s Natural Resourcesis a detailed and fascinating look at indigenous management in California. It appears that similar practices were utilized in many other parts of the continent, and indeed by indigenous people throughout the globe.

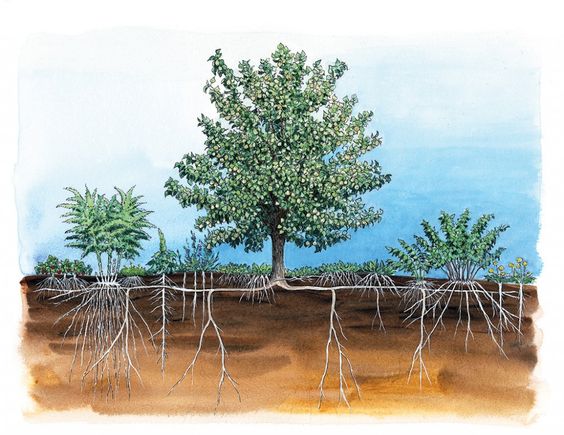

These techniques defy Western definitions of “agriculture” and “wilderness.” They occur on a continuum from intensive cultivation of domesticated annuals to rotational burning of “wild” areas. These practices are summarized as follows.

- Regenerative Harvest: The timing, intensity, frequency, and long term patterning of harvest can have a positive or effect on plants. Native people developed harvest techniques to maximize health and yields of their crop plants. Root crops like camas (Camassia quamash) and sunchoke (Helianthus tuberosus) are examples. Other plants were harvested only once every few years to allow the stands to recuperate.

- Horticultural Practices: “Wild” and cultivated plant populations were managed with burning, irrigation, weeding, tilling, pruning, and coppicing (pruning back to the ground) to maintain healthy and productive stands. Chokecherries and hazels were both fire-pruned to improve fruiting and quality of craft materials.

- Propagation: Plant populations were increased by sowing seed, transplanting, and transporting species or superior varieties to new locations, sometimes far outside of their natural range. Examples include sowing edible grass seeds onto newly burned areas, and the spread by Native people of species like native lotus (Nelumbo lutea) and improved clones of agave (Agave spp.) to new areas.

- Ecosystem Management: Native practices, especially burning, maintained a productive landscape mosaic of desired ecosystems and habitats. The largest scale example is the fire-management of the prairies, large portions of which would have reverted to shrubland, savannah or forest without indigenous burning.

- Cultivation and Domestication: Some crops were taken into active cultivation, sown in settlements or farm fields. Many of these species experienced the increased yields and dependence on humans that we call domestication. Sunflowers (Helianthus annuus), devil’s claw (Proboscidia spp.), and a number of grasses are examples.

| Table: Recorded Horticultural Management Practices Care of “wild” plants in local ecosystems, not “cultivated” in gardens or farms. |

||

| Allium spp. | Wild Onions | weeding, cultivation, burning |

| Amaranthus spp. | Amaranth | sown after burning |

| Apiaceae | Umbel Family Roots | burning |

| Camassia quamash | Camass | weeding, cultivation, harvest rotation |

| Chenopodium berlandieri | Chenopod | sown after burning |

| Cornus sericea | Red Willow, Redtwig Dogwood | burning, pruning, coppicing |

| Corylus americana | American Hazel | burning |

| Corylus cornuta | Beaked Hazelnut | burning |

| Cucurbita foetidissima | Buffalo Gourd | seeding |

| Helianthus tuberosus | Jerusalem Artichoke | weeding |

| Opuntia spp. | Prickly Pear Cactus | pruning, weeding |

| Pinus edulis | Pinyon Pine | pruning, burning |

| Pinus monophylla | Singleaf Pinyon | pruning, burning |

| Poaceae | Wild Grasses | burning, harrowing, seeding |

| Prunus virginiana | Chokecherry | burning |

| Psoralea esculenta | Prairie Turnip | harvest rotation, seeding |

| Quercus gambellii | Gambel Oak | burning |

| Sambucus mexicana | Mexican Elderberry | burning |

| Typha spp. | Cattail | burning |

| Vitis spp. | Wild Grapes | burning, pruned |

| Various species | Wild Greens | burning |

The Importance of Burn-Management

Frequent, low-intensity burns were common throughout North America and are an example of a multifunctional appropriate technology. With sophisticated agro-ecological knowledge and simple tools, Native people were able to increase the productivity of the landscape with minimal effort. Some of the functions of fire include pest and disease control (as in traditional acorn oak management), pruning to rejuvenate useful plant stands, removal of competing “weed” plants, maintenance of desired ecosystem types and successional stages, increased game animal habitat, and prevention of catastrophic fires. Fire appears to have been by far the most widespread indigenous management technique in what is now the U.S.

| Highly Fire-Tolerant Useful Trees and Shrubs These species re-sprout vigorously after fire. |

|

| Celtis reticulata | Netleaf Hackberry |

| Cornus sericea | Red Willow, Redtwig Dogwood |

| Corylus cornuta | Beaked Hazel |

| Prunus americana | American Plum |

| Prunus pumila | Sand Cherry |

| Prunus virginiana | Choke Cherry |

| Quercus gambelii | Gambel Oak |

| Rubus spp. | Raspberry, Thimbleberry |

| Shepherdia spp. | Buffalo Berry |

| Vitis riparia | Riverbank Grape |

| Yucca baccata | Banana Yucca |

Indigenous Management in the Region

Within the prairies, southern Rockies, and Great Basin, intensity of management varied greatly. That the prairies were burned fairly frequently to increase productivity is well documented. Indigenous management of the Rocky Mountain and Great Basin regions, however, is less well known.

From the literature it appears that parts of the Rockies were managed with fire (as well as other practices), while other areas, particularly higher, more desolate sites, may have been largely left to their own devices. Fires may have been on a less frequent cycle than other parts of the country, more like 25-35 years in some areas. As a whole the Rockies and Great Basin were not as intensively managed as coastal California, the prairies, or the agricultural areas of the Southwest and East. Reconstructing management practices for this project has relied largely on accounts of indigenous management of the same species in different regions. Response to fire of profiled species has also been used to cast light on how they would have responded to burn management. A remarkable number of the useful plants profiled benefit from fire management.

Today the Rocky Mountain region provides little of its own food, particularly at higher altitudes. It seems reasonable that Native people also focused their more intensive management efforts on the more fertile and hospitable areas.

A Word About Tense

This article is largely drawn from historical books, including ethnobotanical interviews well over a century old. These books almost uniformly refer to Native people and their practices in the past tense. It is a goal of this publication to serve as the first phase of an investigation into the current state (and potential future) of these species and practices. The profiles describe uses and management in past tense where those practices are only confirmed to have been used in the past, and notes where practices are in contemporary use.

SAMPLE ROCKY MOUNTAIN AND PRAIRIE SPECIES

Piñon Pines: Colorado Piñon (Pinus edulis) and Singleleaf Piñon (P. monophylla). Piñon pines are widespread throughout the southern Rockies and Great Basin regions on slopes, mesas, and canyons. They are generally low growing trees, from 15-20’ high.

Piñon nuts are high in protein, fat, and carbohydrates. They served as a staple food for Native people historically and are still harvested for home and commercial use today by Native people and others. Piñon pines have also been used for firewood, pitch for sealants, medicine, and even basketry (the roots). The trees are very slow growing, not reaching full nut production for one hundred years, but are very long lived. Piñon pines do not produce heavily every year, but have cycles of 3-7 years or more for heavy yields.

There is extensive documentation of Native management of singleleaf piñon in California, in part because many practices continue to the present day. Harvesting involves climbing, shaking or beating the trees, and use of poles to knock down cones. This process knocks down some dead branches and removs shoot tips, encouraging productive new growth.

Younger trees of these pines are killed by fire, and older trees are killed by intense fires. Nonetheless fire management was used to create open woods or savannahs of nut pines. Removal of dead branches, pruning out of all lower branches, and weeding of understory shrubs prevented fire ladders. Raking of needles and removal of kindling in the understory also kept danger of destructive wildfires to a minimum. Controlled, low-intensity burns kept the understory clear and swept through quickly enough not to damage mature trees.

Piñon pine cones take 2-3 years to form, allowing prediction of which groves will be productive several years ahead. Families in California each relied on several geographically distinct groves, as at least one would usually produce in any given year.

The Timbisha Shoshone and Death Valley National Park began a partnership in 2001 to restore traditional indigenous management of singleleaf piñon and mesquite. This collaboration is a model for ecological restoration that acknowledges the realities and benefits of traditional indigenous knowledge.

Riverbank Grape (Vitis riparia). The wild grapes of the western region are vigorous woody vines, growing high in trees along riparian areas and in moister, forests. Riverbank grape grows wild across most of the U.S., and interestingly has become common in urban areas including thickets in vacant lots, and on chain link fences and highway guardrails. They prefer their roots in shade, with the vines climbing and emerging into the sunlight.

The small, tart fruits are borne abundantly. They have seeds and are quite a bit more sour than cultivated grapes, but make fantastic juice, baked goods, and dried fruit. The young green shoot tips and tendrils can be eaten, and the leaves can be used in various ways (like stuffed grape leaves). The vines are very useful in basketry.

The Pueblos cultivated the canyon grape (V. arizonica), and some writers reported indigenous cultivation of native grapes in New England. Tending the Wild reports that in California, management of wild grapes included burning in August, and management by selective harvest and pruning to maximize basketry yields. Grapes are very easy to propagate – sections of vine, cut when dormant, can be stuck in the ground with about 50% growing into new vines. Thus is it easy to imagine that superior wild varieties of grapes were transplanted to new locations in this fashion, particularly as sections of vine were already transported in large numbers for use in basketry.

Raspberry & Thimbleberry (Rubus idaeus & R. parviflorus). Both species are colony-forming spiny shrubs, from 3-5’ high. The native raspberry is found through most of North America except the southeast and Texas, and grows in thickets, old fields, and open woods (in the Rockies up to the timberline). Thimbleberry is found throughout the western and northern US in open woods, often preferring partial shade, at altitudes up to 10,000’.

The berries of both species are widely harvested today, and raspberries are cultivated extensively. Historically, Native American Ethnobotany tells us that American raspberry was the sixth most widely used Native food crop, and thimbleberry the ninth. They were used fresh and dried in a variety of recipes. The leaves of raspberry are medicinal.

Raspberries and thimbleberries are both “fire followers”, re-sprouting vigorously and spreading rapidly after fire. Both would have profited extensively from regular indigenous burn management.

Prickly Pear Cactus (Opuntia spp.). Prickly pears are familiar Western cacti, widespread throughout North America and ranging south through Argentina. Species in this region tend to be low-growing shrubs, often with multiple pads rooting to form colonies. Prickly pears are found in dry prairies and grasslands, and openings in woodlands as well. Native species of the region include beavertail (O. macrorhiza), devil’s tongue (O. humifusa), plains prickly pear (O. polyacantha) and cactus apple (O. engelmannii).

The fruits of all species are edible though some are very small and all wild species are spiny. After de-spining the fruits can be eaten raw, dried and added to stews, or cooked into jellies or preserves. The pads or “nopales”, after despining, are used as a vegetable. The texture and flavor is midway between okra and green beans, and the pads are eaten both raw and cooked in many dishes. The flower petals are also edible and this can be done without impacting fruit production if harvested carefully.

Native people in California developed harvest techniques that boosted productivity. Every time a pad is harvested, two new ones grow. Plants were kept pruned low in this fashion for ease of harvest and maximum productivity, much like contemporary commercial production in Mexico. Cactus pads are incredibly easy to transplant – simply dropping one on the ground is often sufficient to start a new plant. Thus it seems likely that superior varieties were transported to new locations.

Alejandro Casas has studied indigenous management of prickly pears in Mexico and lists numerous management practices. Individual plants with superior flavor or productivity were identified and preferentially harvested. These plants were also used for propagation and transportation of superior material to new locations. When clearing land for agriculture, superior prickly pears were left in place and propagated. Wild plants were also pruned, weeded, and protected from pests.

Spineless forms of tuna or Indian fig (O. ficus-indica) have been cultivated or semi-cultivated in Mexico for thousands of years. Fruits and pads of this species are cultivated on an enormous scale in Mexico, and are popular crops in arid warm climates throughout the world.

Prickly pears are not terribly fire-tolerant, and can be killed by intense fires. Lighter fires burn off the spines, making them vulnerable to herbivores.

Ground Cherry (Physalis spp.) These annual and perennial herbs are closely related to tomatillos. One species or another is found in every one of the lower 48 states and many Canadian provinces. They are found in prairies, disturbed ground, riparian areas, and open woods.

The fruit is sweet, with a flavor somewhere between tomato, pineapple, and strawberry depending on the species. Several domesticated species are widely grown. The green, unripe fruits are toxic. Fruits were used by Native people in many ways, including raw, dried (tasting much like raisins), in sauces with chili peppers, and dried in cakes like chokecherries.

Ground cherries are frequent weeds in farms and gardens, and were encouraged or cultivated by Native people in many regions, including at Mesa Verde. One species (P. longifolia) was cultivated by the Zuni.

Perennial, colony-forming species in the region include the clammy groundcherry (P. heterophylla) and longleaf groundcherry (P. longifolia). The cultivated annual groundcherry (P. pubescens or P. pruinosa), was probably also present in a semi-cultivated state. This species is today known by many names including cape gooseberry, ground cherry, and strawberry tomato.

Prairie Turnip (Psoralea esculenta). Prairie turnips are nitrogen-fixing legumes of dry prairies, and also found in open ground in the eastern Rockies.Their tubers can penetrate very hard ground.

Prairie turnip roots are a bland, starchy, and high in protein. They can be dried and stored for many years, and are still harvested by Native people today.

Prairie turnips were perhaps the most important wild plant food on the prairies, and were traded for corn by the Dakotas and Arikaras. The tubers take 2-4 years to reach harvestable size. Some reports indicate that they were harvested when seeds were ripe, and seeds were planted in the freshly tilled ground where tubers had been dug. “Turnip patches” were managed in this fashion on a multi-year rotation so some were ready for harvest every year.

The tubers of prairie turnip are likely to survive fires and resprout, and the seeds may require or benefit from scarification by fire to begin germination.

Rocky Mountain Bee Plant (Cleome serrulata). Rocky Mountain Bee Plant is an annual native to disturbed ground throughout the prairies, Southwest, Great Basin, and Rocky Mountains. It has very showy pink flowers and an upright growth habit.

The leaves are edible, though they are strong flavored and must be cooked in several changes of water. The seeds can be eaten ground or roasted. The flowers are excellent for attracting pollinators, and it is sown today in post-burn restoration seed mixes to improve pollination and provide food for native insects. Other Cleome species are grown as ornamentals and cut flowers commercially.

This species is known as the “fourth sister” as it was grown in the region as a companion to corn, beans, and squash. Reasons for this practice include improved pollination, attraction of pest control insects, and supplemental food. The Navajo and Pueblo encouraged its growth in their farms and gardens, and its seeds were a staple crop for the Pueblo. The leaves also produce a black dye, which was used for pottery designs. Leaves were also boiled down to a paste, which was stored for later consumption. Apparently this species germinates well after fire.

Eco-Cultural Restoration

This emerging history should also cause us all to reevaluate our concepts of “nature”, “wilderness”, and “agriculture.” Most deciduous forest and prairie in the U.S. and Canada were actively managed, along with extensive evergreen forests in the Southeast, Southwest, and California. What does ecological restoration mean in this context?

It is going to take time to digest these ideas. Meanwhile we can piece together what we can of the management history of the region, though book research, interviews, and experimentation. Fire suppression has turned much of the Rocky Mountain region into a tinderbox. Indigenous management practices reduce the risk of catastrophic fire, while improving habitat and creating a productive broadscale edible landscape. Their restoration serves multiple goals: indigenous community self-determination, decolonizing the diet, and reconnecting people with the land. This hands-on approach to ecology can meet human needs while improving the health of ecosystems – and gives credit to the people who maintained this land for centuries.

To read more (including profiles of over 80 useful plant species with many tables), register for our 5-day Edible Forest Gardens intensive June 3-8 where we will further explore these ideas, or to support upcoming phases of the Woodbine eco-cultural restoration project, visit www.woodbinecenter.org.

The Woodbine Ecology Center is nestled in the foothills of the Rocky Mountains, and features 61 acres of alpine, prairie, and riparian ecosystems. Woodbine brings together people and communities from varied backgrounds to address the fundamental social and ecological issues of our times, creating an egalitarian, just, and sustainable future for the next seven generations.

Eric Toensmeier is the author of Perennial Vegetables and co-author with Dave Jacke of Edible Forest Gardens. His collaboration with Woodbine has resulted in the publication of which this article is an excerpt. His writings, videos, and upcoming workshop schedule can be viewed at www.perennialsolutions.org.