Be sure to sign up for our mailing list.

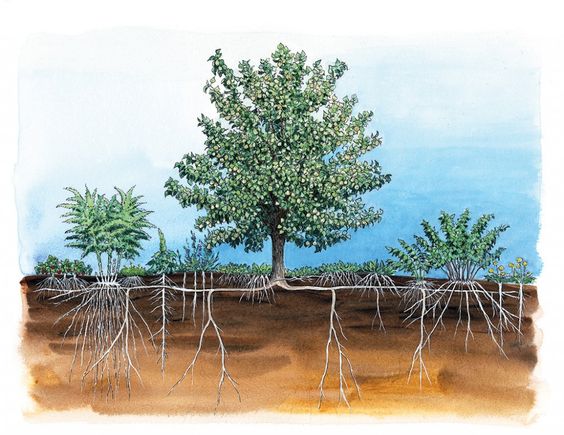

Nitrogen fixing species are a cornerstone of food forestry and other permaculture practices. Through a partnership with symbiotic organisms in their roots, these plants can turn atmospheric nitrogen into nitrogen fertilizers useful to themselves but also becoming available to their neighbors over time through root die back, leaf fall, and chop and drop coppice management. While it does not replace the need to bring in phosphorus, calcium, and other nutrients depleted by harvests, this strategy provides a free source of an essential fertilizer.

Martin Crawford’s Creating a Forest Garden and Nitrogen Fixing Plants for Temperate Climates are excellent resources for calculating the percentage of nitrogen fixtures needed in order to supply all required nitrogen just from plants. Martin estimates this at 25 to 40% of plants in full sun or 50 to 80% of plants in partial shade, depending on the nitrogen needs of the crops being grown.

Now I’m going to throw another wrench into your calculations. I’ve known for some time that the amount of nitrogen fixed varies widely among species, but I recently discovered that the USDA plants database gives information about the amount fixed about many, many species native and naturalized to the United States. Check out their advanced search page to select species for your area. They classify species as HIGH (160+ lbs/acre), MEDIUM (85-160lbs/acre), and LOW (1-85lbs/acre). Note that there are a few species that might represent data entry errors (for example Phragmites is listed as a nitrogen fixer, though I’ve been unable to find another reference to this being the case). I spoke to Martin, who replied that he based his assumptions on an average of 100 kg/ha (88 pounds per acre), basing his estimate in the “medium” category. Thus using “high” nitrogen fixers would allow less space to be used on fertility and more on crops.

It’s interesting to note that many of the most hated naturalized species turn out to be incredibly efficient nitrogen fixers. In fact the “high” nitrogen fixtures category is a rogues gallery of successful dispersive species, like Russian olive (Eleagnus angustifolia), kudzu (Pueraria lobata), and Scotch broom (Cytisus scoparius). I decided to use the database to generate lists of native and non-native nitrogen fixers and categorize them by their efficiency.

Though not all native plant enthusiasts would believe it, I’ve spent decades promoting underutilized native plants. While you may choose to grow non-native pears and peaches in your food forest, there is no particular reason to grow a non-native nitrogen fixer over a native one, with all things being equal. In fact I tend to assume that native plants have a network of visible and invisible relationships with other organisms of all kingdoms, making them more desirable to use whenever possible. I think with the information these databases have provided, we are in an excellent position to promote particular native nitrogen fixers for use in permaculture projects.

In many cases there’s a strong temptation to use nitrogen fixing species which are also edible. I’d like to point out that if you harvest a heavy crop from a nitrogen fixer, you’ve probably taken most of the nitrogen with you, though this may not be the case with fruits as much as it is with beans and leaves. This is another good reason to use efficient native nitrogen fixers even if they’re not edible. On the other hand, if what you really need is nitrogen there are very few native species in the “high” category, making a good case for use of white clover and other non-natives.

With that said, let’s look at a few tables I put together for different regions of the country and then review some of our top native candidates. The astute reader will note that there are very, very few natives in the “high” category. I would speculate that there may be few anywhere, but that they are spreading around very, very successfully.

EASTERN FOREST REGION USA

| HIGH NITROGEN | MEDIUM NITROGEN | LOW NITROGEN | |

| TREES, NATIVE | Robinia pseudoacacia | Catalpa speciosa (*), Gladitsia aquatica (*), Gymnocladus dioicus (*) | |

| TREES, NON-NATIVE | Alnus glutinosa, Elaeagnus angustifolia | Albizia julibrussin | |

| SHRUBS, NATIVE | Alnus incana, A. maritima, A. serrulata, Amorpha fruticosa, A. glabra, Elaeagnus commutata, Morella pensylvanica (=Myrica), Senna marilandica, Shepherdia argentea, S. canadensis | Acacia constricta, Alnus viridis crispa, A. incana rugosa, Ceanothus americanus, Comptonia perigrina, Myrica gale, | |

| SHRUBS, NON-NATIVE | Cytisus scoparius | Caragana arborescens, Elaeagnus umbellata | |

| VINES, NATIVE | Apios americana, Lathyrus japonicus, Wisteria frutescens | Vicia americana | |

| VINES, NON-NATIVE | Pueraria lobata (**) | Lathyrus tuberosus, Vicia cracca | Vicia sativa |

| HERBS, NATIVE | Dalea candida | Amorpha canescens, Dalea formosa, Dryas octopetala, Lespedeza hirta, L. capitata, Hedysarum boreale | Astragalus canadensis, Baptisia tinctoria, Dalea purpurea, Desmanthus illinoiensis, Desmodium paniculatum, D. perplexum, D. tortuosum, Glycyrrhiza lepidota, |

| HERBS, NON-NATIVE | Astragalus cicer, Medicago sativa, Trifolium repens | Lotus corniculatus, Melilotus indicus, Securigera varia (=Coronilla), Trifolium pratense |

*Reports vary on the ability of this species to fix nitrogen but it is identified as doing so in USDA Plants Database, it may be an error.

**235 kg/ha/yr or 207 pounds/acre. Hickman, Jonathan E., Shiliang Wu, Loretta J. Mickey, and Manuel T. Lerdau. “Kudzu (‘‘Pueraria Montana’’) Invasion Doubles Emissions of Nitric Oxide and Increases Ozone Pollution.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, Vol. 107.22, 10115-10119, 2010.

COLORADO

| HIGH NITROGEN | MEDIUM NITROGEN | LOW NITROGEN | |

| TREES, NATIVE | |||

| TREES, NON-NATIVE | Elaeagnus angustifolia | Robinia pseudoacacia | |

| SHRUBS, NATIVE | Alnus incana tenuifolia, Amorpha fruticosa, Ceanothus velutinus, Elaeagnus commutata, Shepherdia argentea, S. canadensis | Cercocarpus ledifolius, C. montanus, | |

| SHRUBS, NON-NATIVE | Caragana arborescens | Purshia stansburiana, P. tridentate, Robinia neomexicana | |

| VINES, NATIVE | Apios americana | Vicia americana | |

| VINES, NON-NATIVE | Vicia sativa | ||

| HERBS, NATIVE | Amorpha canescens, Dalea formosa, Dryas octopetala, Hedysarum boreale | Dalea purpurea, Desmanthus illinoiensis, Glycyrrhiza lepidota, Lupinus argenteus, L. sericeus, | |

| HERBS, NON-NATIVE | Astragalus cicer, Medicago sativa, Trifolium hybridum, T. repens | Melilotus indicus(=Coronilla), Trifolium pratense |

CALIFORNIA

| HIGH NITROGEN | MEDIUM NITROGEN | LOW NITROGEN | |

| TREES, NATIVE | Alnus rubra | Alnus incana, Alnus incana tenuifolia | Morella californica, Olneya tesota, Prosopis pubescens |

| TREES, NON-NATIVE | Elaeagnus angustifolia, Leucaena leucocephala | Albizia julibrussin, Robinia pseudoacacia | |

| SHRUBS, NATIVE | Amorpha fruticosa, Ceanothus velutinus, Shepherdia argentea, S. canadensis, | Alnus rhombifolia, A. viridis sinuata,Ceanothus cordulatus, C. cuneatus, C. fresnensis, C. greggii, C. integerrimus, C. megacarpus, C. papillosus, C. sanguineus, C. ercocarpus ledifolius, C. montanus, Purshia glandulosa, P. stansburiana, P. tridentate, Robinia neomexicana | |

| SHRUBS, NON-NATIVE | Acacia cyclops, A. longifolia, A. melanoxylon, Cytisus scoparius | Caragana arborescens | |

| VINES, NATIVE | Lathyrus japonicus, L. littoralis, L. polyphyllus, | Vicia americana, | |

| VINES, NON-NATIVE | Vicia cracca | ||

| HERBS, NATIVE | Astragalus agrestis, A. filipes, A. lentigenosus, A. purshii, Lupinus arboreus, L. elmeri, L. nevadensis Trifolium longipes, T. macrocephalum, T. wormskioldii | Astragalus Canadensis, A. curvicarpus, Calliandra eriophylla, Ceanothus prostratus, Glycyrrhiza lepidota, Lotus crassifolius, Lupinus argenteus, L. caudatus, L. covillei, L. latifolius | |

| HERBS, NON-NATIVE | Astragalus cicer, Medicago sativa, Trifolium hybridum, Trifolium repens | Lotus corniculatus, Medicago lupulina, Melilotus offocinalis, Trifolium pratense | Caesalpinia gilliesii, Pluchea odorata |

I’d like to profile a few of these US native nitrogen fixers that have broad range of applicability.

Red Alder (Alnus rubra) grows throughout much of Western North America, particularly near the coast. It coppices readily, at least if you start when it is young and do it frequently. Unlike most alders it does not require wet feet. It can also handle some partial shade. Here in my garden in Massachusetts is killed the ground during winter and re-sprouts up to 10 feet high the following year. According to the database, this is the only tree native to North America that fixes over 160 pounds of nitrogen per acre per year. Though you might think that other alders are equally powerful, the genus actually shows up in the high, medium, and low categories.

White Prairie Clover (Dalea candida) is a native clover of the prairies that extends some into the Eastern Forest region. It is used to make a tea, but had never crossed my mind as a particularly significantly given at all of the hundreds of species that seemed to grow in the prairie. Now I know that the USDA database states that this is the only herb native to North America that fixes over 160 pounds of nitrogen per acre per year. Though it wants full sun and (and can handle fairly dry soils), I’m going to try to find room for some of this little–used native that is deserving of a place in the spotlight. Interestingly, like alder, members of this genus can be found in the high, medium and low categories.

False Indigo (Amorpha fruticosa) is native to almost the entire country, though it is considered invasive in Connecticut and a noxious weed in Washington. It can be found from flooded riparian areas to extremely dry conditions, though it always wants a good amount of sun. Studies in the Southeast have shown that under their conditions it can be coppiced up to four times a year for alley cropping chop and drop, though permaculturist Jerome Osentowski reports that it does not coppice well in the high desert of Colorado. It is very widely used in China in agroforestry projects due to its fertility benefits and use as a pesticide. I also personally like that it is neither suckering nor thorny. USDA rates this as a “medium” nitrogen fixer.

Buffalo Berry (Shepherdia argentea) it is native from New York through California. It is fairly drought tolerant and suckers extensively. It can produce very high volumes of edible fruit, though you need both male and female plants to get it. It can coppice, though again Jerome Osentowski reports that at his site it does not do so reliably. USDA rates this as a “medium” nitrogen fixer. The related S. canadensis and Elaeagus commutata are also “medium” N-fixers and widely native.

I’d love to hear about your experiments using the database (or this article) to select native nitrogen fixers for your area. Myself, I feel like I have a new tool to make sure that the nitrogen fixers I select will be the best available for the job. I also feel like I can make a strong case for growing some native species that are currently very underutilized.