Note: this is a piece that was originally to be published in Edible Forest Gardens which I coauthored with Dave Jacke. Yes, there are parts we cut out, it would have been even longer! Dave reviewed and edited that version of this article, though I have substantially updated it here and he is not to blame for any errors that have crept in. This article only addresses the species present in the Matrix of Edible Forest Gardens and, as such, only covers the eastern forest region of the US and Canada from Zones 4-7. Using the hotlinks in this and my last few posts you can construct a similar layout for any climate.

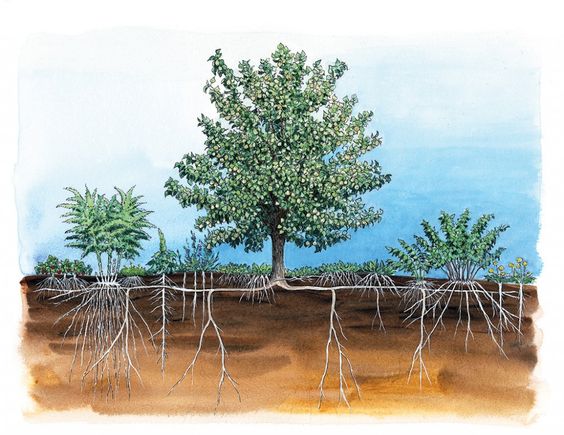

Compositional diversity, the mix of plant species and other living and non-living elements, is a critical element of a stable forest garden ecosystem. This is particularly important in the case of pests and diseases, which frequently only attack closely related plant species. For example, many of the fruits that grow in our climate are from the Rose family, including apples, pears, cherries, peaches, and plums. While these are delicious fruits, they share many pests and diseases, like the dreaded plum curculio. By diversifying the forest garden to include unrelated fruits like kiwi, pawpaw, and persimmon, you can make sure that curculios will not ruin all of your harvest in a bad year. Maximizing compositional diversity can also help to create resource-partitioning guilds, because plants from different families frequently have different strategies and use different nutrients, have different root patterns, or may be otherwise less likely to compete. For example, plants in the lily order tend to have bulbs or tubers close to the soil surface, while many members of the Apiaceae (in the aralia order) are typically taprooted or have deep, branching roots.

Edible fruits of blue bean, Decaisnea fargesii. A member of the very minor Lardizabalaceae family, in the buttercup order Ranunculales. This species is barely related to common forest garden fruits like pears, blueberries, or grapes, sharing few or no pests and diseases with them, and thus an example of omega level diversity in action. Plus it looks super cool!

What is omega level diversity?

In biological language, alpha diversity indicates the total number of species in an ecosystem. While useful, alpha diversity does not tell us anything about the relationships between those species – for all we know, those 100 species could all be oaks, or they could be completely unrelated. Omega level diversity looks at an ecosystem’s diversity at higher levels, measuring a deeper diversity. This “deep” diversity is likely to be the most important contributor of the benefits of compositional diversity. Gardening for omega level diversity (“kinship gardening”) was developed by Alan Kapular and Olafur Brentmar, and carried forward by David Theodoropoulos. In our selection of the species used in the Plant Species Matrix, we worked hard to maximize diversity at the omega level. The relevant distinctions of omega diversity used here are:

- Division. This is the highest level of omega diversity to consider. There are ten great divisions of plants, representing different lineages that diverged many millions of years ago. Some are truly ancient and have dwindled to a small number of species – the most extreme example being the ginkgo, the last representative of its entire division. Of these most ancient groups of plants, which once fed the dinosaurs, the species matrix includes representatives of the bryophyte, conifer, horsetail, ground pine, gingko, and fern divisions (only three divisions are not represented, and these are both small in number of species, and primarily represent tropical species not suited to our climate). However, the vast majority of living species are in the recently evolved (geologically speaking) angiosperm division (the flowering plants) – as are the vast majority of species in the matrix (564 of the 593). Species from six of the ten divisions are featured in Edible Forest Gardens.

- Broad Angiosperm Groupings. These are large groups within the flowering plants that share a common ancestry. The matrix includes representatives of all of these clusters of flowering plants (there is not a direct parallel in the other divisions).

- Order. Orders are groupings of families. The plants within an order may show similarities – as in the Fagales order which includes many families featuring wind-pollinated, nut-bearing trees and shrubs. Both have hardy genera with edible, mucilaginous leaves. The Plant Species Matrix contains representatives of 35 of the 63 plant orders or free-standing families.

- Family. A grouping of related genera. We find increasing similarity between species and genera at the family level. A well-known example is the heath family (Ericaceae), the majority of which are adapted to grow in highly acid environments due to a symbiosis with a group of mycorrhizial fungi. Nonetheless a family may have great variation, including everything from annuals to long-lived forest giants. The matrix includes representatives of 98 of the total of 764 plant families.

- Genus. A grouping of similar species. For example, all the oaks are of the genus Quercus. The Plant Species Matrix contains 319 of the roughly 14,000 world genera.

- Species. The species is the basic unit of plant classification. In theory members of a species are distinct from other species in the genus, and can pollinate each other and cannot pollinate other species. In practice, it can be quite a bit more fluid than that. However, anyone can tell a six-foot highbush blueberry bush (Vaccinnium corymbosum) is different from a low-growing mat of lowbush blueberry (V. angustifolium). Edible Forest Gardens features 593 of approximately 300,000 known plant species.

How to maximize omega diversity in your forest garden.

You may find yourself torn in several directions while selecting species. On the one hand, it is desirable to maximize compositional diversity at the omega level. On the other hand, certain important uses and functions are limited to certain families. Nitrogen fixation is mostly limited to the legumes (Fabales) and certain orders within the rose (Rosales) and beech (Fagales) orders . Specialist nectary plants are generally limited to the Apiaceae, Araliaceae, Saxifragaceae, and portions of the Asteraceae. The great majority of fruit and nut species that can grow in cold climates are in the rose order (Rosales) – in fact, almost a quarter of all species in the Plant Species Matrix are in that order! Thus there is little avoiding the fact that your garden is likely to have heavy representation from these groups of plants.

Beyond this limitation, however, you can make an effort to include as wide a sampling of diversity as possible. Groundcovers, dynamic accumulators, and shelter and nectary plants come from a great diversity of families, and you will find a remarkable range of edibles to choose from as well. When selecting species from the Plant Species Matrix, look up their families in the table below. Keep track of the families, orders, and superorders you are including. Wherever possible, make decisions that maximize diversity. Try to avoid over-dependence on the Rose family in particular, perhaps by substituting persimmons for apples, or one of the edible honeysuckle species for juneberries. We have made an effort to provide you with a diverse assemblage of species to choose from.

Table One: Plant Families listed in Edible Forest Gardens and their Higher-Level Relationships

Families are listed alphabetically. Columns to the right show the order, group, and division to which each family belongs. The numbers in parentheses indicate the number of order, families, genera and species from that group that are represented in the Plant Species Matrix in Edible Forest Gardens. For ease of use I have updated families, orders, and groups here, but not the species and genera themselves.

| FAMILY LISTED in EFG (#genera:#species) | UPDATED FAMILY | ORDER (#families:#genera:#species) | GROUP (#orders:#families: #genera:#species) | DIVISION |

| Aceraceae (1:2) | Sapindaceae | Sapindales (5:5:10) | Eudicots (24:73:184:485) | Angiospermatophyta |

| Actinidiaceae (1:3) | – | Ericales (7:13:29) | Eudicots (24:73:184:485) | Angiospermatophyta |

| Adiantaceae (1:1) | – | – | Pteridophyta (7:13:16) | Pteridophyta |

| Agavaceae (1:1) | Asparagaceae | Asparagales (8:16:28) | Monocots (6:11:34:47) | Angiospermatophyta |

| Alliaceae (2:9) | Amaryllidaceae | Asparagales (8:16:28) | Monocots (6:11:34:47) | Angiospermatophyta |

| Anacardiaceae (1:4) | – | Sapindales (5:5:10) | Eudicots (24:73:184:485) | Angiospermatophyta |

| Annonaceae (1:1) | – | Magnoliales (2:2:2) | Magnoliids (3:6:43:62) | Angiospermatophyta |

| Apiaceae (20:30) | – | Apiales (2:22:37) | Eudicots (24:73:184:485) | Angiospermatophyta |

| Aquifoliaceae (1:1) | – | Aquifoliales (1:1:1) | Eudicots (24:73:184:485) | Angiospermatophyta |

| Araceae (2:2) | – | Alismatales (1:2:2) | Monocots (6:11:34:47) | Angiospermatophyta |

| Araliaceae (2:7) | – | Apiales (2:22:37) | Eudicots (24:73:184:485) | Angiospermatophyta |

| Araucariaceae (1:1) | – | Pinales (3:3:10) | Pinophyta | |

| Aristolochiaceae (1:3) | – | Piperales (2:2:4) | Magnoliids (3:6:43:62) | Angiospermatophyta |

| Asclepiadaceae (1:2) | Apocynaceae | Gentianales (3:4:5) | Eudicots (24:73:184:485) | Angiospermatophyta |

| Asparagaceae (1:1) | Asparagales (8:16:28) | Monocots (6:11:34:47) | Angiospermatophyta | |

| Asphodelaceae (1:1) | Xanthorrhoeaceae | Asparagales (8:16:28) | Monocots (6:11:34:47) | Angiospermatophyta |

| Asteraceae (27:43) | – | Asterales (3:30:48) | Eudicots (24:73:184:485) | Angiospermatophyta |

| Berberidaceae (4:5) | – | Ranunculales (4:8:9) | Eudicots (24:73:184:485) | Angiospermatophyta |

| Betulaceae (2:6) | – | Fagales (5:10:44) | Eudicots (24:73:184:485) | Angiospermatophyta |

| Blechnaceae (1:2) | Pteridophyta (7:13:16) | Pteridophyta | ||

| Boraginaceae (3:5) | – | “Unplaced asterid I” (1:3:5) | Eudicots (24:73:184:485) | Angiospermatophyta |

| Brassicaceae (8:11) | – | Brassicales (1:8:11) | Eudicots (24:73:184:485) | Angiospermatophyta |

| Buxaceae (1:1) | – | Buxales (1:1:1) | Eudicots (24:73:184:485) | Angiospermatophyta |

| Cactaceae (1:1) | – | Caryophyllales (6:13:23) | Eudicots (24:73:184:485) | Angiospermatophyta |

| Calycanthaceae (1:1) | – | Laurales (2:4:4) | Magnoliids (3:6:43:62) | Angiospermatophyta |

| Campanulaceae (2:4) | – | Asterales (3:30:48) | Eudicots (24:73:184:485) | Angiospermatophyta |

| Cannabaceae (1:1) | – | Rosales (7:35:103) | Eudicots (24:73:184:485) | Angiospermatophyta |

| Caprifoliaceae (3:8) | – | Dipsacales (3:5:10) | Eudicots (24:73:184:485) | Angiospermatophyta |

| Caryophyllaceae (2:3) | – | Caryophyllales (6:13:23) | Eudicots (24:73:184:485) | Angiospermatophyta |

| Cephalotaxaceae (1:1) | Taxaceae | Pinales (3:3:10) | Pinophyta | |

| Chenopodiaceae (3:3) | Amaranthaceae | Caryophyllales (6:13:23) | Eudicots (24:73:184:485) | Angiospermatophyta |

| Commelinaceae (1:1) | – | Commelinales (1:1:1) | Monocots (6:11:34:47) | Angiospermatophyta |

| Convallariaceae (7:8) | Asparagaceae | Asparagales (8:16:28) | Monocots (6:11:34:47) | Angiospermatophyta |

| Convolvulaceae (1:2) | – | Solanales (2:2:3) | Eudicots (24:73:184:485) | Angiospermatophyta |

| Cornaceae (1:6) | – | Cornales (1:1:6) | Eudicots (24:73:184:485) | Angiospermatophyta |

| Corylaceae (1:7) | Betulaceae | Fagales (5:10:44) | Eudicots (24:73:184:485) | Angiospermatophyta |

| Crassulaceae (3:5) | – | Saxifragales (3:10:21) | Eudicots (24:73:184:485) | Angiospermatophyta |

| Cyperaceae (1:1) | – | Poales (2:11:13) | Monocots (6:11:34:47) | Angiospermatophyta |

| Dennstaedtiaceae (1:1) | Pteridophyta (7:13:16) | Pteridophyta | ||

| Diapensiaceae (1:1) | – | Ericales (7:13:29) | Eudicots (24:73:184:485) | Angiospermatophyta |

| Dioscoreaceae (1:2) | – | Dioscoreales (1:1:2) | Monocots (6:11:34:47) | Angiospermatophyta |

| Dryopteridaceae (7:7) | Pteridophyta (7:13:16) | Pteridophyta | ||

| Ebenaceae (1:2) | – | Ericales (7:13:29) | Eudicots (24:73:184:485) | Angiospermatophyta |

| Eleagnaceae (3:5) | – | Rosales (7:35:103) | Eudicots (24:73:184:485) | Angiospermatophyta |

| Equisetaceae (1:2) | Equisetales (1:1:2) | Pteridophyta (8:13:16) | Pteridophyta | |

| Ericaceae (7:16) | – | Ericales (7:13:29) | Eudicots (24:73:184:485) | Angiospermatophyta |

| Fabaceae (33:61) | – | Fabales (1:33:61) | Eudicots (24:73:184:485) | Angiospermatophyta |

| Fagaceae (3:18) | – | Fagales (5:10:44) | Eudicots (24:73:184:485) | Angiospermatophyta |

| Fumariaceae (1:1) | Papaveraceae | Ranunculales (4:8:9) | Eudicots (24:73:184:485) | Angiospermatophyta |

| Geraniaceae (1:1) | – | Geraniales (1:1:1) | Eudicots (24:73:184:485) | Angiospermatophyta |

| Ginkgoaceae (1:1) | – | Gingkoales (1:1:1) | Gingkophyta | |

| Grossulariaceae (1:10) | – | Saxifragales (3:10:21) | Eudicots (24:73:184:485) | Angiospermatophyta |

| Hemerocallidaceae (1:3) | Xanthorrhoeaceae | Asparagales (8:16:28) | Monocots (6:11:34:47) | Angiospermatophyta |

| Hyacinthaceae (1:3) | Asparagaceae | Asparagales (8:16:28) | Monocots (6:11:34:47) | Angiospermatophyta |

| Hydrophyllaceae (1:1) | Rubiaceae | Gentianales (3:4:5) | Eudicots (24:73:184:485) | Angiospermatophyta |

| Illiciaceae (1:1) | Schisandraceae | Austrobaileyales (2:2:2) | Unclassified (1:2:2:2) | Angiospermatophyta |

| Iridaceae (2:2) | – | Asparagales (8:16:28) | Monocots (6:11:34:47) | Angiospermatophyta |

| Juglandaceae (2:9) | – | Fagales (5:10:44) | Eudicots (24:73:184:485) | Angiospermatophyta |

| Lamiaceae (16:26) | – | Lamiales (3:19:29) | Eudicots (24:73:184:485) | Angiospermatophyta |

| Lardizabalaceae (1:1) | – | Ranunculales (4:8:9) | Eudicots (24:73:184:485) | Angiospermatophyta |

| Lauraceae (3:3) | – | Laurales (2:4:4) | Magnoliids (3:6:43:62) | Angiospermatophyta |

| Liliaceae (3:8) | – | Liliales (3:5:10) | Monocots (6:11:34:47) | Angiospermatophyta |

| Lobeliaceae (1:1) | Campanulaceae | Asterales (3:30:48) | Eudicots (24:73:184:485) | Angiospermatophyta |

| Lycopodiaceae (1:1) | Lycopodiopsida (1:1:1) | Lycopodiopsida | ||

| Magnoliaceae (1:1) | Magnoliales (2:2:2) | Magnoliids (3:6:43:62) | Angiospermatophyta | |

| Malvaceae (5:6) | – | Malvales (2:6:8) | Eudicots (24:73:184:485) | Angiospermatophyta |

| Melastomataceae (1:1) | – | Myrtales (3:3:4) | Eudicots (24:73:184:485) | Angiospermatophyta |

| Meliaceae (1:1) | – | Sapindales (5:5:10) | Eudicots (24:73:184:485) | Angiospermatophyta |

| Moraceae (2:5) | – | Rosales (7:35:103) | Eudicots (24:73:184:485) | Angiospermatophyta |

| Myricaceae (2:4) | – | Fagales (5:10:44) | Eudicots (24:73:184:485) | Angiospermatophyta |

| Myrtaceae (1:1) | – | Myrtales (3:3:4) | Eudicots (24:73:184:485) | Angiospermatophyta |

| Onagraceae (1:2) | – | Myrtales (3:3:4) | Eudicots (24:73:184:485) | Angiospermatophyta |

| Oxalidaceae (1:4) | – | Oxidales (1:1:4) | Eudicots (24:73:184:485) | Angiospermatophyta |

| Passifloraceae (1:1) | – | Malphigiales (2:2:5) | Eudicots (24:73:184:485) | Angiospermatophyta |

| Phytolaccaceae (1:1) | – | Caryophyllales (6:13:23) | Eudicots (24:73:184:485) | Angiospermatophyta |

| Pinaceae (1:8) | – | Pinales (3:3:10) | Pinophyta (1:3:3:10) | Pinophyta |

| Poaceae (10: 12) | – | Poales (2:11:13) | Monocots (6:11:34:47) | Angiospermatophyta |

| Polemoniaceae (1:4) | – | Ericales (7:13:29) | Eudicots (24:73:184:485) | Angiospermatophyta |

| Polygonaceae (4:10) | – | Caryophyllales (6:13:23) | Eudicots (24:73:184:485) | Angiospermatophyta |

| Polypodiaceae (1:2) | Pteridophyta (7:13:16) | Pteridophyta | ||

| Polytrichaceae (1:1) | Bryophyta (1:1:1) | Bryophyta | ||

| Portulacaceae (2:5) | – | Caryophyllales (6:13:23) | Eudicots (24:73:184:485) | Angiospermatophyta |

| Pyrolaceae (1:2) | Ericaceae | Ericales (7:13:29) | Eudicots (24:73:184:485) | Angiospermatophyta |

| Ranunculaceae (2:2) | – | Ranunculales (4:8:9) | Eudicots (24:73:184:485) | Angiospermatophyta |

| Rhamnaceae (3:4) | – | Rosales (7:35:103) | Eudicots (24:73:184:485) | Angiospermatophyta |

| Rosaceae (22:83) | – | Rosales (7:35:103) | Eudicots (24:73:184:485) | Angiospermatophyta |

| Rubiaceae (2:2) | – | Gentianales (3:4:5) | Eudicots (24:73:184:485) | Angiospermatophyta |

| Rutaceae (1:2) | – | Sapindales (5:5:10) | Eudicots (24:73:184:485) | Angiospermatophyta |

| Sambucaceae (1:1) | Adoxaceae | Dipsacales (3:5:10) | Eudicots (24:73:184:485) | Angiospermatophyta |

| Sapindaceae (1:1) | – | Sapindales (5:5:10) | Eudicots (24:73:184:485) | Angiospermatophyta |

| Saururaceae (1:1) | – | Piperales (2:2:4) | Magnoliids (3:6:43:62) | Angiospermatophyta |

| Saxifragaceae (6:6) | – | Saxifragales (3:10:21) | Eudicots (24:73:184:485) | Angiospermatophyta |

| Schisandraceae (1:1) | – | Austrobaileyales (2:2:2) | Unclassified (1:2:2:2) | Angiospermatophyta |

| Scrophulariaceae (1:1) | – | Lamiales (3:19:29) | Eudicots (24:73:184:485) | Angiospermatophyta |

| Smilacaceae (1:1) | – | Liliales (3:5:10) | Monocots (6:11:34:47) | Angiospermatophyta |

| Solanaceae (1:1) | – | Solanales (2:2:3) | Eudicots (24:73:184:485) | Angiospermatophyta |

| Styracaceae (1:1) | – | Ericales (7:13:29) | Eudicots (24:73:184:485) | Angiospermatophyta |

| Thelypteridaceae (1:1) | Pteridophyta (7:13:16) | Pteridophyta | ||

| Tiliaceae (1:2) | Malvaceae | Malvales (2:6:8) | Eudicots (24:73:184:485) | Angiospermatophyta |

| Trilliaceae (1:1) | Melianthiaceae | Liliales (3:5:10) | Monocots (6:11:34:47) | Angiospermatophyta |

| Ulmaceae (2:3) | – | Rosales (7:35:103) | Eudicots (24:73:184:485) | Angiospermatophyta |

| Urticaceae (2:2) | – | Rosales (7:35:103) | Eudicots (24:73:184:485) | Angiospermatophyta |

| Valerianaceae (1:1) | – | Dipsacales (3:5:10) | Eudicots (24:73:184:485) | Angiospermatophyta |

| Verbenaceae (2:2) | – | Lamiales (3:19:29) | Eudicots (24:73:184:485) | Angiospermatophyta |

| Violaceae (1:4) | – | Malphigiales (2:2:5) | Eudicots (24:73:184:485) | Angiospermatophyta |

| Vitaceae (1:4) | – | Vitales (1:1:4) | Eudicots (24:73:184:485) | Angiospermatophyta |

Table Two: Relative Representation of Divisions

This is the highest level of diversity. Note we still have relatively few of these except ferns and conifers. Note that the cycad division is strictly tropical and thus cannot be represented in a cold climate forest garden.

| Marchiantophyta (liverworts) | 0 |

| Anthoceratophyta (hornworts) | 0 |

| Bryophytes (mosses) | Mosses (1) |

| Lycopiodopsida (clubmosses) | Clubmosses (1) |

| Pteridophytes (ferns and horsetails) | Ferns (14) |

| Horsetails (1) | |

| Cycads | 0 |

| Gingkphytes (Gingko) | Gingkos (1) |

| Coniferophytes (Conifers) | Conifers (10) |

| Gnetophytes (jointfirs) | 0 |

| Angiospermatophytes | Flowering plants (565) |

Table Two: Relative Representation of Flowering Plant Groups and Orders

Note that some orders are strictly aquatic or tropical and thus cannot be represented in a cold climate forest garden.

| Unclassed Angiosperms | Amborellales (0) |

| Nymphaeales (0) | |

| Austrobaileyales (2) | |

| Magnoliids | Piperales (4) |

| Laurales (4) | |

| Magnoliales (2) | |

| Canellales (0) | |

| Chloranthales (0) | |

| Monocots | Alismatales (2) |

| Asparagales (30) | |

| Dioscoreales (2) | |

| Liliales (10) | |

| Commelinales (2) | |

| Poales (13) | |

| Zingiberales (0) | |

| Arecales (0) | |

| Dasypogonaceae (0) | |

| Pandanales (0) | |

| Petrosaviales (0) | |

| Acorales (0) | |

| Eudicots | Boraginaceae (5) |

| Araliales (37) | |

| Aquifoliales (1) | |

| Asterales (48) | |

| Brassicales (11) | |

| Buxales (1) | |

| Caryophyllales (23) | |

| Cornales (6) | |

| Dipsicales (10) | |

| Ericales (29) | |

| Fabales (60) | |

| Fagales (45) | |

| Gentianales (6) | |

| Geraniales (1) | |

| Lamiales (29) | |

| Malphigiales (5) | |

| Malvales (8) | |

| Myrtales (4) | |

| Oxidales (4) | |

| Ranunculales (9) | |

| Rosales (102) | |

| Sapindales (10) | |

| Saxifragales (21) | |

| Solanales (3) | |

| Vitales (4) | |

| Ceratophyllales (0) | |

| Sabiaceae (0) | |

| Proteales (0) | |

| Trochodendrales (0) | |

| Gunnerales (0) | |

| Cucurbitales (0) | |

| Celastrales (0) | |

| Zygophyllales (0) | |

| Huerteales (0) | |

| Picraminiales (0) | |

| Crossosomotales (0) | |

| Dilleniaceae (0) | |

| Berberidopsidales (0) | |

| Santalales (0) | |

| Garryales (0) | |

| Escalloniales (0) | |

| Paracryphiales (0) | |

| Bruniales (0) |

In review, how did we do in selecting for omega diversity? Well pretty good in fact. We could improve at the all-important division level. As I now know both liverworts and hornworts fix nitrogen, I might encourage people to add those divisions. Cycads won’t grow here, but one could add the Gnetophyte Ephedra, which Dave and I actually considered but were turned off by its toxicity, it is really more of a medicinal than a food. If you were to do all this in your cold climate forest garden you could represent 9 of the 10 great living divisions of plants!

We did pretty well on the magnoliids and unclassed angiosperms as well, not much I’d add there to be honest.

Monocots? You might add Acorus calamus in a wet sunny spot to gain the Acorales, but much more exciting are the hardy edible gingers from Zingiberales, especially Zingiber mioga and Curcuma zedoaria.

Zedoary (Curcuma zedoaria), a hardy ginger relative used as a spice and a rhizomatous starch source, would add the Zingiberales order to your sampling of diversity. Hardy to zone 6b and a shade-lover, this should be much more widely grown in cold-climate forest gardens.

As for the Eudicots, we have pretty good representation. From Cucurbitales you could add Cucurbita foetidissima, the buffalo gourd, and perhaps the weedy eastern native Melothria pendula.

Review of Omega-Level Categories

Interestingly, humans can eat very few of the non-flowering plants (mosses, horsetails, ferns, conifers, etc.). It has been speculated that, while mammals diversified at the same time as the flowering plants, we have never learned to make good use of these ancient groups that came about in the age of dinosaurs or before. In forest gardens, we can make use of many of these plants as groundcovers, as well as consuming the nuts of ginkgos and several conifer genera. The numbers in parentheses indicate how many species from the genus are listed in Edible Forest Gardens.

DIVISION: BRYOPHYTA (Mosses)

This group of spore-bearing plants emerged 750-500 million years ago, making them among the earliest land plants.

Family: Polytrichiaceae

Genera: Polytrichium (1)

Ancient and primitive, but still quite successful, many moss groundcovers are well adapted to the shady conditions of the forest garden. Here’s Polytrichum commune, photo by Sten via Wikimedia Commons.

DIVISION: LYCOPODIOPSIDA (Clubmosses)

Not as old as you might think, the spore-bearing lycopodiums began to diversify as much as 200 million years ago.

Family: Lycopodiaceae

Genus: Lycopodium (1)

A Lycopodium species in the understory of an old-growth hardwoods forest. It can grow more densely, to make a tighter groundcover.

A Lycopodium species in the understory of an old-growth hardwoods forest. It can grow more densely, to make a tighter groundcover.

Horsetail (Equisetum arvense), an ancient and extremely vigorous eastern native groundcover. Thoroughly unrelated to all other forest garden groundcovers except the distantly to the ferns, making it a good choice for preventive pest and disease control. Has medicinal uses and serves as a base for a fungicidal spray.

Horsetail (Equisetum arvense), an ancient and extremely vigorous eastern native groundcover. Thoroughly unrelated to all other forest garden groundcovers except the distantly to the ferns, making it a good choice for preventive pest and disease control. Has medicinal uses and serves as a base for a fungicidal spray.

DIVISION: PTERIDOPHYTA (Ferns & Horsetails)

A large group of spore-bearing plants once featuring dominant tree species, now thriving in the understory of conifers and flowering plants.

Order: Equisetales

Family: Equisetaceae

Genera: Equisetum (2)

The single remaining genus of an ancient group of plants. Dynamic accumulators, with some fine groundcovers.

Fern Orders

Ferns visually make a forest garden feel like a forest. They leaf out late in the spring, and thus make fine companions to spring ephemeral plants. I confess I’ve not yet found the perfect contemporary listing of fern relationships. For now I’ll just list their families here.

Family: Adiantaceae

Genera: Adiantum (1)

Family: Polypodiaceae

Genera: Polypodium (2)

Family: Blechnaceae

Genera: Woodwardia (2)

Family: Dryopteridaceae

Genera: Athyrium (1), Dryopteris (1), Gymnocarpium (1), Matteuccia (1), Onoclea (1), Polystichum (1), Thelypteris (1)

Family: Thelypteridaceae

Genera: Thelypteris (1)

Family: Dennestaedtiaceae

Genera: Dennstaedtia (1)

Ostrich fern (Matteuccia struthiopteris), an eastern native fern with edible shoots, also a fine groundcover for moist and/or shady areas.

DIVISION: GINKGOPHYTA (Ginko)

The sole remaining species in what was once a diverse and important division of plants – imagine a day far in the future when only one species of flowering plant remains to represent all the flowers of today’s world! About 200 million years old.

The edible nuts and horrible-smelling, rash-causing “fruit” of ginkgo. Note that “stinkless” female varieties are available in the nursery trade.Photo by jy mit Kamera via Wikimedia Commons.

Order: Ginkgoales

Family: Ginkgoaceae

Genera: Ginkgo (1)

Korean nut pine (Pinus koraensis), an edible nut pine showing cones on 30-year old seedling trees.

DIVISION: CONIFEROPHYTA (Conifers)

Perhaps 350-300 million years old. Commonly associate with ectomycorrhizal fungi.

Order: Araucariales

Family: Araucariaceae

Genera: Araucaria (1)

Monkey puzzle, Araucaria araucana, has enormous cones with edible nuts. Photo by scott.zona via Wikimedia Commons.

Order: Pinales

Family: Pinaceae

Genera: Pinus (8)

Order: Taxales

Family: Cephalotaxaceae

Genera: Cephalotaxus (1)

The conifers are an exception among the non-flowering plants in providing a large number of edible species. As evergreens, they are also important wildlife cover plants.

Japanese Plum Yew (Chephalotaxus harringtonia), a conifer in the order Taxales. A shrub with edible fruits and nuts, tolerating substantial shade.

Japanese Plum Yew (Chephalotaxus harringtonia), a conifer in the order Taxales. A shrub with edible fruits and nuts, tolerating substantial shade.

DIVISION: ANGIOSPERMATOPHYTA (Flowering Plants)

Emerged perhaps 140 million years ago, thought to have co-evolved with the great diversification of insects as pollinators and herbivores.

Unclassed Angiosperms

Order: Austrobaileyales

Family: Schisandraceae

Genera: Illicium (1), Schisandra (1)

Though its home in the angiosperms is not yet clear, Florida star anise (Illicium floridanum) is a marvelous shade-loving eastern native spice plant hardy through zone 7 and even a bit colder.

Though its home in the angiosperms is not yet clear, Florida star anise (Illicium floridanum) is a marvelous shade-loving eastern native spice plant hardy through zone 7 and even a bit colder.

Magnoliids

This broad group came into being 200-130 million years ago. Scientists are still clarifying the magnoliids relationship to the monocots and eudicots. Most of the magnoliids were formerly classed with the eudicots in a large group called the dicots, which is no longer a contemporary category.

Pawpaw (Asimina triloba), best of the Magnoliids for the cold-climate forest garden.

Pawpaw (Asimina triloba), best of the Magnoliids for the cold-climate forest garden.

Order: Piperales

Family: Aristolochiaceae

Genera: Asarum (3)

Family: Saururaceae

Genera: Houttuynia (1)

Wild ginger (Asarum canadense), a native medicinal woodland groundcover in the Piperales.

Order: Laurales

Family: Calycanthaceae

Genera: Calycanthus (1)

Family: Lauraceae

Genera: Lindera (1), Persea (1), Sassafrass (1)

Order: Magnoliales

Family: Annonaceae

Genera: Asimina (1)

Family: Magnoliaceae

Genera: Magnolia (1)

Despite being in different families, pawpaw, spicebush, sassafras, and Carolina allspice all have strongly aromatic leaves that are toxic, and each has their own butterfly species that can tolerate the toxins.

Carolina allspice (Calycanthus floridus), a typical Laurales order shrub with spicy aromatic parts and a special relationship with butterflies.

Carolina allspice (Calycanthus floridus), a typical Laurales order shrub with spicy aromatic parts and a special relationship with butterflies.

Monocots

A large cluster of plants, with the common trait of a single cotyledon leaf emerging at germination. Tending to be herbaceous in cold climates, and featuring many useful bulb, tuber, and leaf crops.

Order: Alismatales

Family: Araceae

Genera: Amorphophallus (1), Colocasia (1)

Edible leaves of taro (Colocasia esculenta), thought of as tropical but hardy to zone 7b. Needs multiple years to for tuber yield in short-season areas but a fine leaf crop for wet sun to partial shade.

Welsh onion (Allium fistulosum), one of many excellent perennial onions for the forest garden.

Order: Asparagales

Family: Amaryllidaceae

Genera: Allium (8), Triteleia (1)

Family: Asparagaceae

Genera: Asparagus (1), Camassia (3), Clintonia (1), Maianthemum (1), Medeola (1), Polygonatum (1), Smilacina (1), Streptopus (2), Uvularia (1), Yucca (1)

Family: Xanthorrhoeaceae

Genera: Asphodeline (1), Hemerocallis (3)

Family: Iridaceae

Genera: Crocus (1), Iris (1)

Order: Dioscoreales

Family: Dioscoreaceae

Genera: Dioscorea (2)

Impressive tuber of Chinese yam (Dioscorea opposita).

Impressive tuber of Chinese yam (Dioscorea opposita).

Order: Liliales

Family: Liliaceae

Genera: Erythronium (1), Fritillaria (1), Lilium (6)

Family: Smilacaceae

Genera: Smilax (1)

Family: Trilliaceae

Genera: Trillium (1)

Kamchatka lily, Fritillaria camschatcensis, has edible bulbs. Photo by Σ64 via Wikimedia Commons.

Order: Commelinales

Family: Commelinaceae

Genera: Commelina (1), Tradescantia (1)

Virginia dayflower, Commelina erecta, is representative of the Commelinales – looking like a grass with insect-pollinated flowers instead of wind-pollinated. Photo by Assaf Shtilman via Wikimedia Commons.

Order: Poales

Family: Cyperaceae

Genera: Carex (1)

Family: Poaceae

Genera: Andropogon (1), Arundinaria (1), Chasmanthium (1), Phyllostachys (3), Sasa (1), Secale (1), Semiarundinaria (1), Sorghum (1), Tripsacum (1), Triticum (1)

Edible shoots of Phyllostachys bamboos. Many Poales associate with endophytic fungi which live inside the leaves and help minimize herbivory. Almost half of these species have the efficient C4 metabolism (warm-season grasses).

Edible shoots of Phyllostachys bamboos. Many Poales associate with endophytic fungi which live inside the leaves and help minimize herbivory. Almost half of these species have the efficient C4 metabolism (warm-season grasses).

Eudicots

Most of the group formerly known as dicots live here now. The eudicots have two cotyledons at germination like the more primitive Magnoliids, but among other differences they have distinctive three-parted pollen grains. This is the largest group of flowering plants, which is itself the largest division of plants.

Unplaced Family: Boraginaceae

Genera: Borago (1), Mertensia (1), Symphytum (3)

Though unplaced within the eudicots, comfrey is one of the most commonly planted forest garden herbs. This is the hybrid “Hidcote blue,” a running dwarf that is a great groundcover and, like other comfreys, is a dynamic accumulator that provides great habitat for beneficial insects and arthropods.

Though unplaced within the eudicots, comfrey is one of the most commonly planted forest garden herbs. This is the hybrid “Hidcote blue,” a running dwarf that is a great groundcover and, like other comfreys, is a dynamic accumulator that provides great habitat for beneficial insects and arthropods.

Order: Araliales

Family: Apiaceae

Genera: Bunium (1), Conopodium (1), Cryptotaenia (2), Cymopteris (2), Erigenia (1), Eryngium (1), Foeniculum (1), Heracleum (1), Levisticum (1), Ligusticum (3), Lomatium (4), Myrrhis (1), Osmorhiza (2), Perideridia (1), Pimpinella (1), Polytaenia (1), Sium (1), Taenidia (1), Thaspium (2), Zizia (2)

Family: Araliaceae

Genera: Aralia (5), Panax (2)

Sweet cicely (Myrrhis odorata) is a classic Apiaceae umbel flower, attracting beneficial insects in mid-spring. All parts are licorice-flavored, with the green seeds a special favorite.

Sweet cicely (Myrrhis odorata) is a classic Apiaceae umbel flower, attracting beneficial insects in mid-spring. All parts are licorice-flavored, with the green seeds a special favorite.

Order: Aquifoliales

Family: Aquifoliaceae

Genera: Ilex (1)

The native Ilex glabra has desirable charcteristics for attracting insect-eating birds: it is evergreen, thicket-forming, and has bird food berries. Gardeners in zone 7 might add the caffeine-producing yaupon, Ilex vomitoria.

Order: Asterales

Family: Asteraceae

Genera: Achillea (2), Antennaria (2), Arnoglossum (1), Artemisia (3), Aster (2), Balsamorhiza (1), Bellis (1), Chamaemelum (1), Chrysogonum (1), Cichorium (1), Conoclinium (1), Coreopsis (3), Echinacea (1), Erigeron (1), Helianthus (5), Heliopsis (1), Hieraceum (1), Lactuca (1), Parthenium(1), Petasites(1), Scorzonera (1), Senecio (2), Silphium (3), Smallanthus (1), Solidago (3), Taraxacum (1), Vernonia (1)

Family: Campanulaceae

Genera: Campanula (3), Platycodon (1)

Family: Lobeliaceae

Genera: Lobelia (1)

Scorzonera (Scorzonera hispana) in the Asteraceae. Though not of the subtribe that attracts beneficial insects, worth growing for the edible roots, leaves, and especially the cooked flowerstalks when the buds are still closed.

Order: Brassicales

Family: Brassicaceae

Genera: Arabis (1), Armoracia (1), Brassica (1), Bunias (1), Cardamine (3), Crambe (1), Diplotaxis (2), Nasturtium (1)

The edible “broccolettas” of Crambe cordifolia are similar in flavor to annual brassicas.

The edible “broccolettas” of Crambe cordifolia are similar in flavor to annual brassicas.

Order: Buxales

Family: Buxaceae

Genera: Pachysandra (1)

Groundcover of native Pachysandra procumbens. Including native Pachysandra is a great example of maximizing omega diversity – this species is barely related to anything else in the forest garden, letting us sample its entire order and perhaps minimizing pest and disease pressure as well.

Groundcover of native Pachysandra procumbens. Including native Pachysandra is a great example of maximizing omega diversity – this species is barely related to anything else in the forest garden, letting us sample its entire order and perhaps minimizing pest and disease pressure as well.

Order: Caryophyllales

Family: Cactaceae

Genera: Opuntia (1)

Family: Caryophyllaceae

Genera: Pseudostellaria (1), Stellaria (2)

Family: Amaranthaceae

Genera: Atriplex (1), Beta (1), Chenopodium (1)

Family: Phytolaccaceae

Genera: Phytolacca (1)

Family: Polygonaceae

Genera: Oxyria (1), Polygonum (3), Rheum (3), Rumex (3)

Family: Portulacaceae

Genera: Claytonia (3), Montia (2)

The edible leaves of good King Henry (Chenopodium bonus-henricus) are classic Caryophyllales.

The edible leaves of good King Henry (Chenopodium bonus-henricus) are classic Caryophyllales.

Order: Cornales

Family: Cornaceae

Genera: Cornus (6) The edible fruits of Cornus mas, Cornelian cherry dogwood.

The edible fruits of Cornus mas, Cornelian cherry dogwood.

Order: Dipsicales

Family: Caprifoliaceae

Genera: Linnaea (1), Lonicera (4), Viburnum (3)

Family: Valerianaceae

Genera: Centranthus (1)

Family: Sambucaceae

Genera: Sambucus (1)

Red valerian (Centranthus ruber), a favorite perennial vegetable of Martin Crawford, from the Dipsicales.

Red valerian (Centranthus ruber), a favorite perennial vegetable of Martin Crawford, from the Dipsicales.

Order: Ericales

Family: Actinidiaceae

Genera: Actinidia (3)

Family: Diapensiaceae

Genera: Galax (1)

Family: Ebenaceae

Genera: Diospyros (2)

Family: Ericaceae

Genera: Arbutus (1), Arctostaphylos (1), Epigaea (1), Gaultheria (3), Gaylussacia (2), Rhododendron (1), Vaccinium (7)

Family: Polemoniaceae

Genera: Phlox (4)

Family: Pyrolaceae

Genera: Chimaphila (2)

Family: Styracaceae

Genera: Halesia (1)

Highbush blueberry (Vaccinium corymbosum) is a delicious representative of the Ericales.

Order: Fabales

Family: Fabaceae

Genera: Acacia (1), Amorpha (3), Amphicarpaea (1), Apios (3), Astragalus (4), Baptisia (2), Caragana (3), Cercis (1), Clitoria (1), Colutea (1), Cytisus (1), Desmodium (2), Genista (3), Gleditsia (1), Glycyrrhiza (3), Hedysarum (1), Indigofera (1), Lathyrus (4), Lespedeza (2), Lupinus (2), Maakia (1), Medicago (1), Phaseolus (1), Prosopis (1), Psoralea (1), Robinia (3), Sophora (1), Strophostyles (1), Stylosanthes (1), Thermopsis (1), Trifolium (2), Vicia (3), Wisteria (3)

A string of edible tubers of timpsila or prairie turnip (Psorales esculenta), a nitrogen fixing Fabales species. The legumes are a large family, well represented in the edible forest garden as nitrogen-fixers. Legumes tend to be poisonous or spiny to defend their nitrogen-rich foliage, but also include many of the most important food plants in the world.

A string of edible tubers of timpsila or prairie turnip (Psorales esculenta), a nitrogen fixing Fabales species. The legumes are a large family, well represented in the edible forest garden as nitrogen-fixers. Legumes tend to be poisonous or spiny to defend their nitrogen-rich foliage, but also include many of the most important food plants in the world.

Order: Fagales

Family: Betulaceae

Genera: Alnus (4), Betula (2)

Family: Corylaceae

Genera: Corylus (7)

Family: Fagaceae

Genera: Castanea (3), Fagus (2), Quercus (13)

Family: Juglandaceae

Genera: Carya (4), Juglans (5)

Family: Myricaceae

Genera: Comptonia (1), Myrica (3)

Hybrid hazel (Corylus), classic Fagales. An important order for cold climate food forests, featuring edible nuts and actinorhizal nitrogen fixers.

Hybrid hazel (Corylus), classic Fagales. An important order for cold climate food forests, featuring edible nuts and actinorhizal nitrogen fixers.

Order: Gentianales

Family: Apocynaceae

Genera: Asclepias (2)

Family: Rubiaceae

Genera: Houstonia (1), Mitchella (1)

Family: Hydrophyllaceae

Genera: Hydrophyllum (1)

Native edible-leaf Hydrophyllum loves shady forest gardens.

Native edible-leaf Hydrophyllum loves shady forest gardens.

Order: Geraniales

Family: Geraniaceae

Genera: Geranium (1)

Wild geranium (Geranium maculatum) is a fine native groundcover from the Geraniales. Here’s another example of a groundcover, as good as any other, that can stand in as representative for an entire order.

Wild geranium (Geranium maculatum) is a fine native groundcover from the Geraniales. Here’s another example of a groundcover, as good as any other, that can stand in as representative for an entire order.

Order: Lamiales

Family: Lamiaceae

Genera: Agastache (1), Blephilia (2), Calamintha (1), Clinopodium (1), Cunila (1), Lycopus (1), Melissa (1), Mentha (6), Monarda (2), Origanum (1), Pycnanthemum (2), Rosmarinus (1), Salvia (1), Satureja (1), Stachys (3), Thymus (1)

Family: Scrophulariaceae

Genera: Veronica (1)

Family: Verbenaceae

Genera: Verbena (1), Vitex (1)

Bee balm (Monarda didyma) is typical of the Lamiales – aromatic and somewhat weedy. An important group for forest gardens. In cold climates the Lamiales tend to have similar niches as aromatic herbaceous generalist nectary species. Also frequently adapted to the partial shade found in forest gardens. Many are tea or culinary plants.

Bee balm (Monarda didyma) is typical of the Lamiales – aromatic and somewhat weedy. An important group for forest gardens. In cold climates the Lamiales tend to have similar niches as aromatic herbaceous generalist nectary species. Also frequently adapted to the partial shade found in forest gardens. Many are tea or culinary plants.

Order: Malphigiales

Family: Passifloraceae

Genera: Passiflora (1)

Family: Violaceae

Genera: Viola (4)

The flowers and fruit of maypop (Passiflora incarnata) are like nothing else in the cold-climate forest garden. Another major tropical fruit order with few cold-climate offerings, though both hardy passionfruit and violets are great to have.

The flowers and fruit of maypop (Passiflora incarnata) are like nothing else in the cold-climate forest garden. Another major tropical fruit order with few cold-climate offerings, though both hardy passionfruit and violets are great to have.

Order: Malvales

Family: Malvaceae

Genera: Alcea (1), Althaea (1), Callirhoe (1), Hibiscus (1), Malva (2), Tilia (2)

Purple poppy-mallow (Callirhoe involucrata) has the mucilaginous edible leaves typical of its family, plus edible roots. A nice groundcover too. Malvaceae for cold climates tend to be mucilaginous edible leaf crops.

Purple poppy-mallow (Callirhoe involucrata) has the mucilaginous edible leaves typical of its family, plus edible roots. A nice groundcover too. Malvaceae for cold climates tend to be mucilaginous edible leaf crops.

Order: Myrtales

Family: Melastomataceae

Genera: Rhexia (1)

Family: Myrtaceae

Genera: Eucalyptus (1)

Family: Onagraceae

Genera: Epilobium (2)

Fireweed (Epilobium angustifolium), perhaps our best cold-climate edible in the Myrtales. A minor group in cold climate forest gardens, though featuring many fantastic fruits like guava and related genera for warmer climates.

Fireweed (Epilobium angustifolium), perhaps our best cold-climate edible in the Myrtales. A minor group in cold climate forest gardens, though featuring many fantastic fruits like guava and related genera for warmer climates.

Order: Oxidales

Family: Oxalidaceae

Genera: Oxalis (4)

Violet wood sorrel (Oxalis violacea), with edible leaves and bulbs showing the characteristic sour flavor of this family.

Violet wood sorrel (Oxalis violacea), with edible leaves and bulbs showing the characteristic sour flavor of this family.

Order: Ranunculales

Family: Berberidaceae

Genera: Berberis (1), Jeffersonia (1), Mahonia (2), Podophyllum (1)

Family: Lardizabalaceae

Genera: Decaisnea (1)

Family: Ranunculaceae

Genera: Aquilegia (1), Coptis (1)

Family: Papaveraceae

Genera: Dicentra (1)

Creeping Oregon grape (Mahonia repens), an evergreen groundcover with edible fruit. Also contains medicinal berberine, found in several families in this order.

Creeping Oregon grape (Mahonia repens), an evergreen groundcover with edible fruit. Also contains medicinal berberine, found in several families in this order.

Order: Rosales

Family: Rosaceae

Genera: Amelanchier (5), Aronia (2), Cercocarpus (1), Chaenomeles (1), Crataegus (4), Cydonia (1), Dryas (1), Fragaria (5), Geum (2), Malus (3), Mespilus (1), Potentilla (1), Prunus (24), Pyrus (2), Rosa (5), Rubus (14), Sanguisorba (3), Sorbus (4), Waldsteinia (1), x Sorbaronia (1), x Sorbocrataegus (1), x Sorbopyrus (1)

Family: Cannabaceae

Genera: Humulus (1)

Family: Eleagnaceae

Genera: Eleagnus (2), Hippophae (2), Shepherdia (1)

Family: Moraceae

Genera: Cudrania (1), Morus (4)

Family: Rhamnaceae

Genera: Ceanothus (2), Hovenia (1), Zizyphus (1)

Family: Ulmaceae

Genera: Celtis (2), Ulmus (1)

Family: Urticaceae

Genera: Laportaea (1), Urtica (1)

A classic Rosaceae, Asian pear or nashi (Pyrus spp.) has edible fruit. This is an excellent family of edible fruits, but as they share many pests and diseases, increasing omega-level diversity can help safeguard against crop losses. Within the broader Rosales order, the Eleagnanaceae, Rosaceae, and Rhamnaceae contain all many of the actinorhizal nitrogen fixers.

Order: Sapindales

Family: Anacardiaceae

Genera: Rhus (4)

Family: Sapindaceae

Genera: Acer (2), Xanthoceras (1)

Family: Meliaceae

Genera: Toona (1)

Family: Rutaceae

Genera: Zanthoxylum (2)

Not all of our nuts are in the Fagales. This is yellowhorn (Xanthoceras sorbifolium) of the Sapindales. A very important tropical fruit order featuring citrus, mangoes and more, quite a bit more minor in temperate forest gardens.

Not all of our nuts are in the Fagales. This is yellowhorn (Xanthoceras sorbifolium) of the Sapindales. A very important tropical fruit order featuring citrus, mangoes and more, quite a bit more minor in temperate forest gardens.

Order: Saxifragales

Family: Crassulaceae

Genera: Hylotelephium (1), Rhodiola (1), Sedum (3)

Family: Saxifragaceae

Genera: Chrysosplenium (1), Darmera (1), Heuchera (1), Mitella (1), Saxifraga (1), Tiarella (1)

Family: Grossulariaceae

Genera: Ribes (10)

Ribes: delicious diversity. From top left: gooseberry (R. uva-crispa), josta (R. x culverwellii), red and white currant (R. sativum), clove currant (R. odoratum), black currant (R. nigrum). Ribes is a very important shade fruiting genus in forest gardens, while the Saxifragaceae are useful as specialist nectary groundcovers.

Ribes: delicious diversity. From top left: gooseberry (R. uva-crispa), josta (R. x culverwellii), red and white currant (R. sativum), clove currant (R. odoratum), black currant (R. nigrum). Ribes is a very important shade fruiting genus in forest gardens, while the Saxifragaceae are useful as specialist nectary groundcovers.

Order: Solanales

Family: Convolvulaceae

Genera: Ipomoea (2)

Family: Solanaceae

Genera: Physalis (1)

Native perennial ground cherry (Physalis longiflora) has a fruit used as a vegetable like so many Solanaceae (tomato, eggplant, tomatillo, bell pepper etc.). This order contains many important world vegetables (like tomato and sweet potato), though its importance to cold climate forest gardens is relatively minor and confined to sunny clearings and early succession phases.

Native perennial ground cherry (Physalis longiflora) has a fruit used as a vegetable like so many Solanaceae (tomato, eggplant, tomatillo, bell pepper etc.). This order contains many important world vegetables (like tomato and sweet potato), though its importance to cold climate forest gardens is relatively minor and confined to sunny clearings and early succession phases.

Order: Vitales

Family: Vitaceae

Genera: Vitis (4)

Small superorder, supplying us with grapes and muscadines. Here’s a lovely purple-leaf grape, a variety of the European grape Vitis vinifera.

Small superorder, supplying us with grapes and muscadines. Here’s a lovely purple-leaf grape, a variety of the European grape Vitis vinifera.

A Challenge

So can you get a member of every one of these orders in your forest garden? Can you add some more not listed here? How wide a net can you cast? Omega diversity is not the only criteria we need, but like emphasizing native species, can help bring some underutilized species to our attention. Dave and I determined that omega diversity was important enough to guide our species selection, and we hope it will do the same for you. Enjoy!