Excerpted from Paradise Lot: Two Plant Geeks, One Tenth of an Acre, and the Making of an Edible Garden Oasis in the City

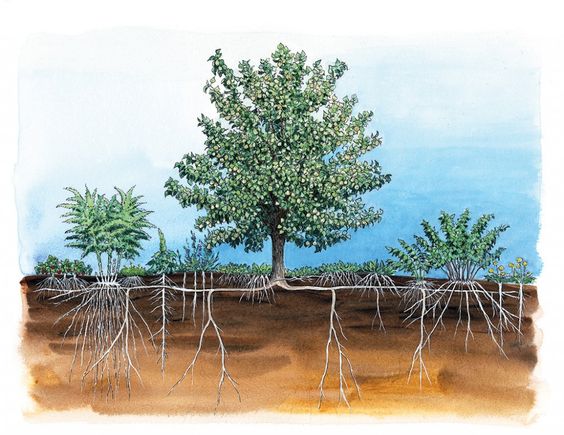

As perennial vegetable season dries up, berries are coming into full swing. Foraging for fresh fruit in the backyard was a key goal in our garden and this is reflected in the diversity and abundance of berries we enjoy. Within two to three years, all of our berries were yielding well and many were filling in to form nice patches. There’s nothing better than walking out the back door and feasting on five or six different kinds of berries as you make your way through the garden. Jonathan and Meg next door love them on their cereal every morning. We’ve cooked all kinds of dishes with them, but in general, that’s too much work for me: nothing is a satisfying as filling up a handful of berries and shoving them into my mouth, eating them right out in the sunshine.

Our first berries of spring are honeyberries or haskap (Lonicera caerulea), which are ripen in May. You need at least two varieties for pollination, and though our first one died, its replacement caught up. We enjoy these small sweet and sour blue delights, a harbinger of harvests to come.

Soon after honeyberry harvest is over, strawberries (Fragaria x anasana) come along. I never liked strawberries growing up; now I know it’s because the quality of strawberries sold in the store is nothing like a fresh fragrant strawberry from the garden. We rotate our strawberry beds slowly through the garden, giving each planting three years in each location, and starting a new one every spring. We started with everbearing varieties, but then turned our focus to heavy June-bearing types since we have plenty of other fruit during other times of the year.

Alpine strawberries (F. vesca alpina) which pack all the flavor of a quart of strawberries into each tiny fruit, start fruiting around the time, continue through early July and come on again to some degree in the fall. They’re so small and make just a few fruits each day so we plant them along the borders of our pathways to remind us to take advantage of them.

Some years our strawberry harvest is poor. Perhaps it is a cold, wet year and disease is affecting our yields, or perhaps we didn’t do a good job of weeding or planting out our new bed the year before and yields suffer as a result. In those years we rely heavily on our goumi (Elaeagnus multiflora) whose small red cherries are tart and astringent until dead ripe, at which point they’re quite nice. Our goumi bears heavily, so we learned to process them with our steam juicer to take full advantage of the harvest. Of course, goumi is also welcome in our garden because it is a nitrogen fixer and grows (and bears) extremely vigorously in some of our worst compacted clay soils and in partial shade.

Later in June we get a second flush of berry species. I have come to appreciate our “Gerardi dwarf” mulberry (Morus macroura). Most wild mulberries are watery and insipid, but good cultivated mulberry varieties have firmness and tartness in with the sweet. Our dwarf mulberry bush bears for about six weeks; the fruit are large and make for nice eating. It’s not quite as dwarf as we had thought and we spend a lot of time pruning it back in winter and keeping it under control in summer by lopping off branches to feed to our silk worms. Left to its own devices it might spread to ten feet high and wide—not quite the “dwarf” we had in mind.

It wouldn’t be June without juneberries (multiple species of the genus Amelanchier, also known as serviceberry, sarvisberry, saskatoon, shadblow, and other names). We planted our two “Regent” saskatoons, a cross between the treelike Amelanchier alnifolia and dwarf A. stolonifera, in a prime location between the greenhouse and the beach plums, a spot with ideal sun and our least terrible soil. “Regent” bears heavily and, like all juneberries, has knockout flowers in spring. Little did we know that the fruits of this variety are somewhat dry and mealy (like all the alnifolias I’ve ever eaten), though the bushes are an ideal five-foot size. Jonathan and I ate them out of a sense of duty but Meg and Marikler never felt constrained by that, and the fruits were just not getting eaten. Even the birds were not enthusiastic. We moved the “Regents” to the front yard a few years ago so that at least their pretty flowers would be visible to passersby and because, as far as we’re concerned, the neighborhood children can eat all the berries they want. Much more to our liking is a wild clone of running juneberry, which we dug up from a nearby natural area a few years ago and transplanted in with our blueberries. The berries are a little smaller, but sweet and juicy. This wild juneberry doesn’t grow more than two feet tall but it spreads by runners and is filling in the gaps between our half high blueberries. [Note – the flavor of “Regent” has since grown on me. And some “Regent” fruits I had in Colorado were outstanding, perhaps they want a less humid climate to reach perfection.]

Towards the end of June, our red and white currants (Ribes rubrum) come on. We found some clones (“Red Lake,” “Blanca,” and “Pink Champange”) that are nice for eating raw. At first, I was the only one in the house who liked them, but I passed on my secret of lightly chewing the fruit but leaving the seeds intact and the others started to enjoy them as well. The seeds are a bit too large and textured for such a juicy fruit as farm as I’m concerned, but this little trick gets totally around the issue. Once Megan cooked down the red currents to make a sauce; she, Jonathan, and Marikler had it over ice cream and were truly hooked. Since then we have planted more varieties. Red and white currents bear well even in full shade, which means they’re taking on an increasingly prominent role beneath our mimosa and fruit trees as they mature.

July brings ridiculous riches of berries, many belonging, like currants, to the genus Ribes. Gooseberries (R. uva-crispa) are a house favorite. Most of the varieties we grow have spines, making the harvest quite painful, but their flavor is like a grape from another dimension. We grow about six varieties and enjoy all of them for fresh eating when ripe and in baked desserts when still green, tart, and firm.

Black currants (R. nigrum) ripen in July as well. These were an acquired taste for me, though I enjoyed beverages and desserts made with them many times. In 1997, I traveled to England with Dave to research Edible Forest Gardens. We stayed with Robert Hart who literally wrote the book on temperate climate forest gardening. At the time we were visiting, a local bakery would trade Robert his fruit for their desserts. I ate black currant crumble for several meals. When fully ripened their musk and spiciness is emboldened by a sweet and juicy essence. I nibble on them as I walk by them in my own garden, though I don’t eat a double handful the way I do with red and white currents and season.

Black currants and gooseberries were crossed to create the jostaberry (R. x culverwellii). Jostas are happy in our garden—even in pretty serious shade under Norway maples—and produce well for us. Plus they are thornless! Though tart until fully ripe, I can’t get enough of these spicy sour delights.

Our final member of the genus Ribes is clove currant (R. odoratum). Clove currants have clove-scented yellow flowers that bloom around the same time as forsythia; unlike forsythia, however, the flowers are followed by edible fruit. Our “Crandall” clove currant has fruits that are much larger than wild clove currants, though I think their skin is tougher and I prefer the smaller wild forms. Jonathan says ”Crandall” is his favorite fruit and the neighbors also love them.

Our clove currants grow on a narrow strip of terrible soil between our driveway and our neighbors’ driveway. This area is hot and dry in the summer, and in the winter it is buried under several feet of snow. This is where we moved the “Regent” juneberries that we weren’t totally in love with. Our goal is to create an edible hedge; we also fruited a sand cherry (Prunus besseyi) there. The species is native from Cape Cod west through the Rocky Mountains and we grow two prostrate forms (“Pawnee Butte” and “Select Spreader”) that serve as groundcovers. The black fruits ripen in July and have a rich, subtle flavor. I look forward to them fruiting more heavily in the future.

Blueberries are next in July’s carnival of abundance. We grow a couple of hybrid “half-high” varieties (Vaccinium hybrids) and some lowbush blueberries (V. angustifolium) as well. So far, we have not had to net them the way our rural friends have to. Birds in the country will eat every berry before they ripen, but in the city, it seems like our birds mostly don’t know what to do with them. Our blueberries have grown slowly and we have messed around with the pH several times trying to give them a jump start. They eventually began to bear pretty well, though Megan and Marikler still go to a pick your own operation to get enough berries to freeze for winter. Generally, I’m pleased with our strategy of planting small numbers of a great diversity of fruits to have the longest possible season, but when it comes to blueberries I wish we had a second tenth of an acre to dedicate to them.

When we moved in we noticed right away that there was a patch of feral raspberries (Rubus idaeus) behind our neighbor’s shed. The branches that hung over the fence were the first fruits we ate in our garden. The fruits were small and sweet with a delicate flavor. When we purchased and planted a fancy-named variety we were disappointed to find that the fruits, though large, were tough and bland. We ripped them out and transplanted in some of our neighbors feral plants. But our favorite raspberry is the golden “Anne”, which I’d ordered from a nursery after tasting it in several gardens and falling in love. Jonathan calls them “mango berries.” I agree that they taste fantastic, but I also love the insight they offer into an elegant pest-control strategy. Birds can be pests in raspberry patches, but they wait for the fruit to turn red to know that it is ripe. Yellow fruit doesn’t register on their radar. This also applies to yellow cherries and perhaps other fruits and represents an interesting alternative to netting your fruit.

The berry season peters out for a while after raspberry season, so we plan to add black raspberries (R. occidentalis), thimbleberries (R. parviflorus) , and thornless blackberries (R. fruticosus) to help fill in the sad two whole weeks of the summer when, in a bad grape year, we sometimes have almost no fresh fruit. [Note – the black rapberries and thornless blackberries have been a huge success since this was written in 2011, but thimbleberry has yet to produce a single fruit].

Raspberries return again for a halfhearted season in September and October. Late September is also the ripening time for one of my favorite little–known fruits. Ground cherries (Physalis spp.) are sweet relatives of tomatillos and tomatoes. A papery husk encloses a golden orb and the flavor is often compared to a combination of pineapple and cherry tomato. We grew annual ground cherries (P. pruinosa) for several years, but over time switched to the native perennials. Native perennial species like clammy and longleaf groundcherry (P. heterophylla and P. longifolia respectively) have smaller, firmer fruit with the more complex flavor. They come into season somewhat late, but I have picked ripe fruit off the plants as late as December 21st.

I’m not sure if wintergreen (Gaultheria procumbens) berries are our first or last fruit of the year. They ripen in late fall and remain viable under the snow all winter. You can dig down to them under the snow, or wait until the ground thaws in March. Wild forms have tiny fruits, but I noticed a number of years ago that cultivated ornamental forms like “Very Berry” and “Christmas” that have been selected for larger flowers also have much larger fruit, more of it, and share the same wintergreen flavor as the wild forms. Marikler thinks the berries taste like Pepto Bismal, but I like them. Our late berry season also include a bit of lingonberry (Vaccinium vitis-idaea) fruit, a tiny six inch shrub related to cranberries. The fruits are like tiny cranberries though we have not yet had enough to do much with them.